The Price of Free Energy

It happens more often than I’d like to admit. My car’s fuel gauge reads less than a quarter tank... again. While there is enough gas to last me another day, I always ask myself when should I fill up? Do I get gas now and be responsible (my mom would say yes), or do I hope gas prices will go down a bit in a few days and fill up for cheap later (unlikely)? Perhaps I should go to Costco and get an even bigger discount. Thankfully, I have many options to buy as much gas as I can afford from my choice of sellers. This isn’t always the case.

What would happen if I couldn’t buy any gasoline, at any price?

We in highly developed nations are used to buying whatever goods, in this case gas, we want whenever we want from a large number of producers. Usually the prices of gasoline are roughly the same across stations in a given county or state. But big price disruptions can occur - hello 1973 OPEC oil crisis. As many of us found in North America through 2021 and 2022, average regular grade gas prices doubled from a national average of $2.24 in January 2021 to a high of $4.76 in June 2022 (EIA Data) due to post-pandemic supply issues and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

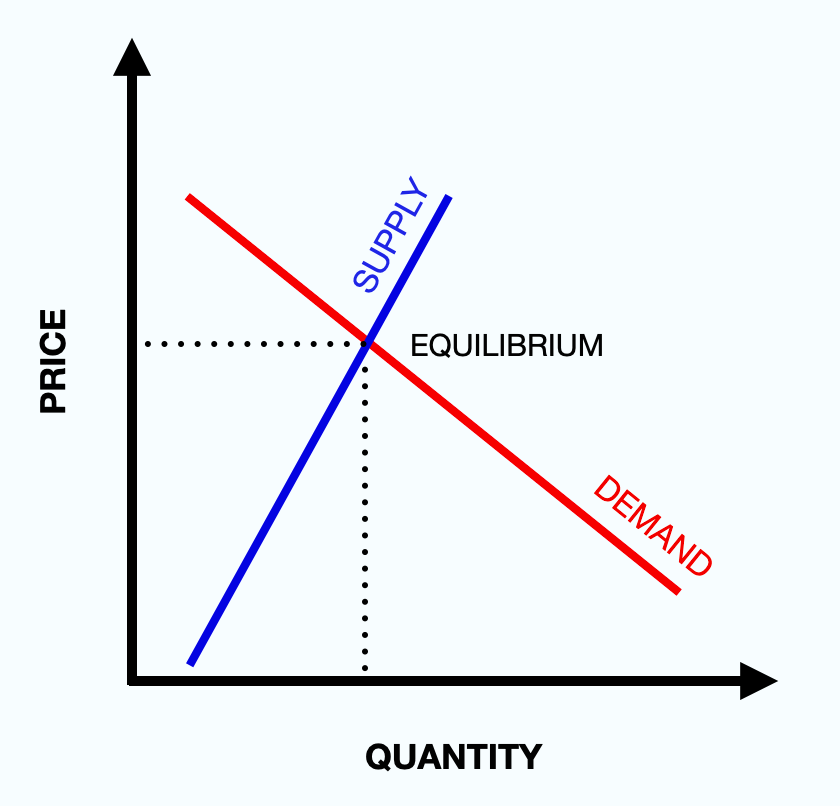

Now this may seem like an issue. Why should you be paying more for the same product a few days later. What’s changed? What looks like a bug in the system, high prices, is actually a positive feature in disguise. That's one of the Jekyll-Hyde tradeoffs of competitive market places. Prices go up and down to balance the supply of gas with the demand for gas. Only in extreme global events, like the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, does supply of essential products get completely shut off and prices go crazy. Even then, the high prices help identify solutions to provide new supply to alleviate the shortage.

European natural gas prices went vertical in autumn of 2022 as Russian gas supplies were cut off from much of Europe. Germany, dependent on Russian natural gas, had to scramble to meet their energy needs. They even built a new liquified natural gas terminal in record time to relieve the energy stress and re-opened closed coal mines to support the electric grid. Prices for natural gas went up and Germany had to respond by finding alternatives, coal, and building new infrastructure to access different suppliers, the new LNG terminal. Surprising everyone, they suspended the closure of their remaining nuclear plants. The high natural gas price signaled to Germany, and other EU members, to change their policies in order to reduce the price of natural gas imported to the continent. The price system worked, even though the EU instituted a price cap on natural gas in an attempt to alleviate some price pains.

Why does Europe, and Germany in particular, depend on imported natural gas? Germany began its energy turnaround, Energiewende, in 2010 to transition the traditionally coal and nuclear dependent German electric grid to a 100% renewable grid in the future. As they build more renewable sources like wind and solar, they also have to import natural gas to supply the petrochemical industry and provide electricity when the renewable sources are producing less electricity. The disruption in the EU energy markets demonstrated a fundamental issue with renewable energy sources:

You can't buy more wind when you need it.

You can buy more batteries for storage, you can buy pumped storage, you can buy more wind turbines, and you can buy more transmission infrastructure, you can even buy backup fossil fueled power plants, but you still can't buy more wind. You can't buy more sunlight either. You can only buy substitutes - or go without. One of the key praises for sources of energy like solar and wind is the use of "free" energy from the sun: light and wind. The total price of renewable energy is often hidden in the infrastructure required to support renewables when they aren’t producing. While we can count on the sun to shine for a few more billion years or so (fingers crossed, but after 2020 anything is possible at this point), we can't count on the wind or sunshine as much as we need to maintain a reliable electric grid. Grid scale battery tech is coming down in cost, but sufficient battery deployment to address wind and solar variability has yet to be achieved - and may never be achieved in many markets.

The Germans can’t buy more energy from wind or solar when they need it. What they can do is buy more natural gas, coal, and nuclear, which they have done. This is hardly the green energy transition they or anyone else hoped for. Unlike buying gasoline at the pump, they can’t pick and choose how much wind or solar energy they produce when they need it. Yet, that kind of dynamic can be expected from a grid that is overweight in demand blind sources such as solar and wind without sufficient storage. You have to substitute that power source with something else, and all too often that something else ends up being the dirtiest fossil power we can produce - like Germany's lignite coal plants. How different would the energy situation in Germany look if Germany decided to keep more of their excellent clean nuclear plants operating?